It initially seems a no-brainer that the ability to charge at home using domestic power tariffs that are cheaper — as well as a far more convenient user experience — than public charging should be a major driver in switching to all-electric. And that said logic would extend to having access to the cheapest domestic power being the most attractive to switch away from gasoline to BEVs.

On a total cost of ownership (TCO) basis, the cheaper the power for your home charging, the greater the savings from plugging in rather than filling up. But the US, at a state level, is largely making a mockery of this rationale.

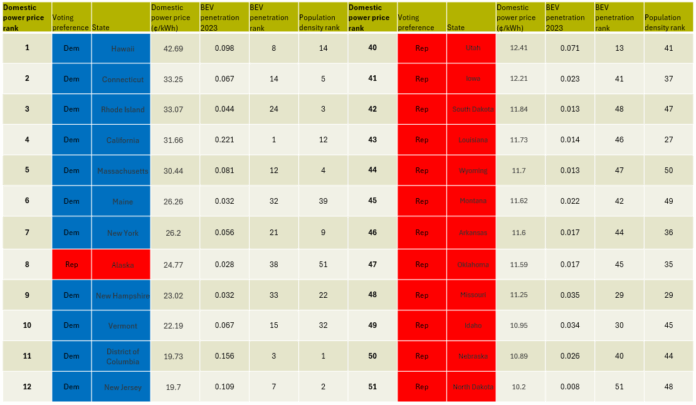

The table below (see Fig.1) shows the 12 states (including the District of Colombia) with highest average domestic power tariffs, as per EIA date for February this year, and the 12 states with the lowest. It also looks at where these states rank in terms of BEV penetration, as per Alliance for Automotive Innovation data for 2023.

The table shows that the dozen states where power is most expensive also includes four of the eight states — California, DC, Hawaii and New Jersey — where BEV penetration rates are highest. Only three states — Alaska, New Hampshire and Maine — that have the priciest domestic power tariffs are in the bottom half in terms of adoption of all-electric vehicles.

At the other end of the scale, in states where power is the cheapest, BEV adoption is largely sluggish, despite the TCO benefits these bargain electrons should offer. Only in Utah, where 7.1pc of new registrations in 2023 being BEV places it 13th in the adoption rankings, do we find a state with the lowest tariffs in the top half of the all-electric penetration tables.

In fact, nine of the dozen states with the cheapest average power price for household end-users are also in the bottom 12 for share of BEV sales in their mix. Most notably, at an average of 10.2¢/kWh, North Dakota consumers have the lowest-cost power in the US, but are also the most reluctant to buy BEVs, at less than 0.8pc of the 2023 new vehicles mix.

Not just price at play

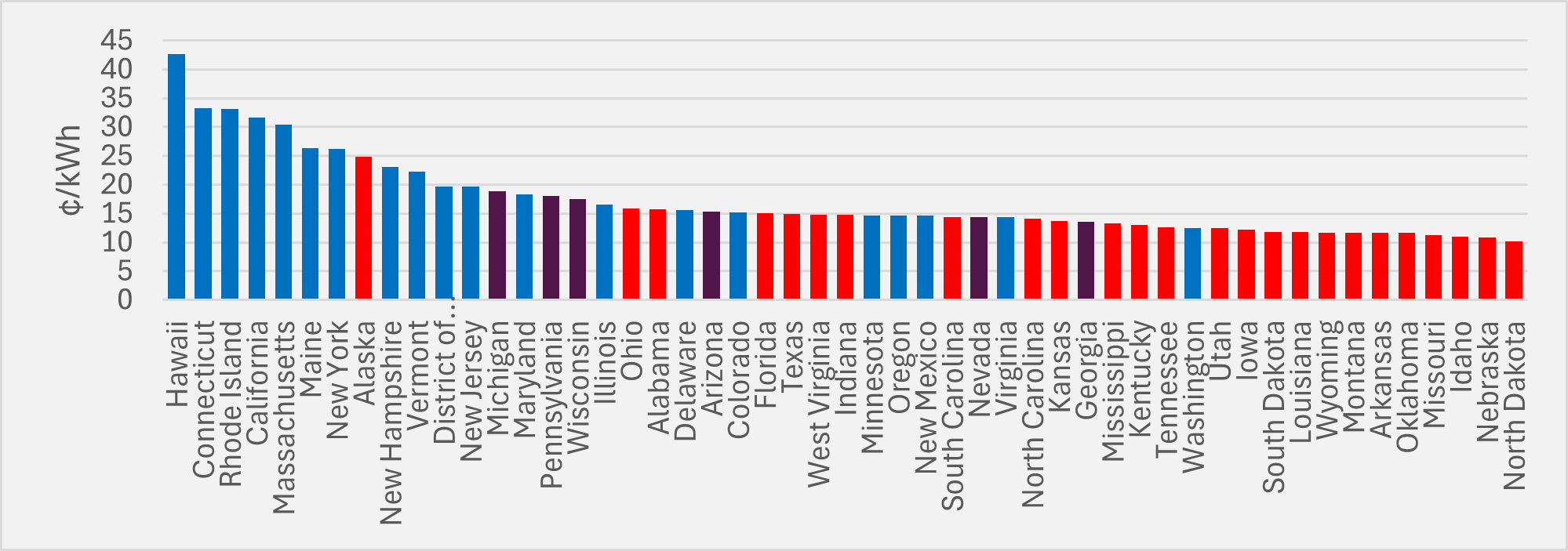

So, what’s going on? To some extent, political polarisation and BEVs getting caught up in the US’ seemingly endless culture wars is playing a part. The chart at the top (see main image), showing BEV adoption rates by state and how those states voted in the last two presidential elections, tells its own story.

Blue bars represent states that opted for Biden and Harris in 2020 and 2024, respectively. And they are largely clustered on the left of the chart, illustrating that solidly Democratic states tend to have greater appetite to switch to all-electric. Maroon bars represent the five state that swung from Biden in ’18 to Trump in ’24, while red bars are those states that Trump carried in both polls.

The best maroon state is Nevada in fifth, but you have to go all the way down to Utah to find the top genuinely red state. And the right of the chart is a sea of red, with the 18 states with lowest BEV penetration rates all having been carries by Trump last time out, just one of which (Michigan) having gone for Biden in the previous election. New Hampshire is the blue state with lowest appetite for all-electric.

Geography may also be another factor. What Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, Montana, Oklahoma, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming have in common as well as voting Republican and not buying many BEVs despite having cheap electricity is that they are among the 17 least densely populated states.

This plays into two genuine obstacles to BEV adoption. One is that inhabitants of these more rural states are potentially more likely to regularly undertake journeys of the length where range anxiety is an actual, rather than psychological issue, compounded by the real risk posed by public EV charging in these parts of the country remaining spotty.

The second is that drivers in these states may also be more regularly using utility vehicles for their initial purpose. E-trucks do not yet have comparable towing capabilities to their ICE equivalents, so those who actually need to push to the limits of a vehicle’s capacity for work would have a genuine reason to stick to gasoline, even with the carrot of cheap power if they bought a BEV.

This could help offer another reason why Alaska is relatively loath to embrace all-electric — 2.8pc penetration placing it 38th in 2023 — expensive power, Republican-leaning and by far the least densely populated state. And it might explain why true-blue Maine ranks 32nd for BEV uptake, being the state with the 12th lowest population density.

But there are outliers not easily explained by political leaning or being more or less urban. New Hampshire and Rhode Island stand out as perhaps having fewer BEV purchases than might be suggested by their Democratic voting intentions and relatively dense populations. As mentioned above, there is no obvious reason — beyond the cheap power that does not yet seem to drive consumer behaviour elsewhere — why Republican-voting and rural Utah has high BEV penetration for a red state. Conversely, Louisiana languishing in the bottom six for BEV buying despite solidly midtable in terms of population density is not obvious.

The chart below (see Fig.2) shows that, for whatever reasons, Democratic states tend to have higher household power prices than Republican states. So, currently, BEV uptake in the US — with Washington a notable exception — has been most successful despite having to make most progress against the drag of higher power prices.

But what if that situation flipped around? Instead of high prices being a disadvantage to BEV ownership on a TCO basis, what if higher power prices made owning a BEV more attractive?

That is what largescale rollout out of V-2-X could promise. Instead of your vehicle simply being a price taker, the ability to integrate your vehicle’s battery into the power grid could make it materially cheaper to light, air condition and — if you switch away from gas/heating oil/propane — heat your home relative to having an ICE vehicle with a tank of gasoline sitting in the driveway.

And where would such economics be most favourable? In areas where the price of electricity is 20-35¢/kWh, not in places where it is 10-14¢/kWh.

EV inFocus has long believed that V-2-X is hugely overlooked in terms of a catalyst for BEV adoption. Once people start recognising the value of having an optimisation tool sat on or adjacent to their property that will reduce their household bills, compared to an ICE vehicle that cannot offer the same utility, we move swiftly to a Netflix versus Blockbuster or Iphone versus Nokia moment.

That, in the US, the greatest savings will be largely concentrated in states where political leaning and vehicle use cases are already probably more conducive to all-electric is only going to make what is already to some extent a two-speed market even more marked in its difference in velocity.